✦

I’ll Do My Best

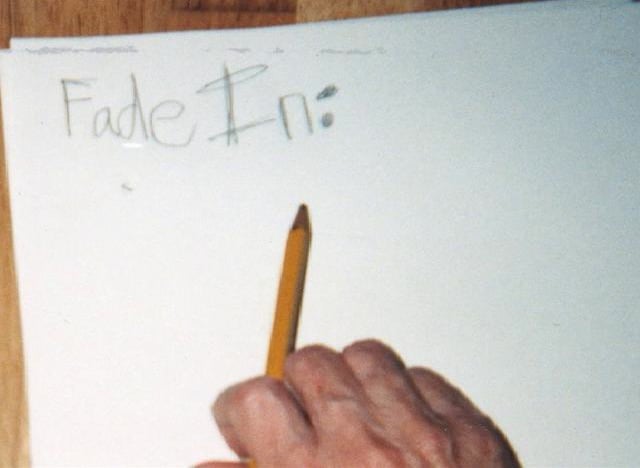

Okay, you can’t see this. You can’t see anything but words, words, words. Humph. Well, I guess it’s on me. abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz. Yeah, all right. Sure. These are my tools. Oh yeah, you can’t hear this either. Damn, and you can’t hear me. There may be people around you talking or music or a TV or something and just abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz to compete. I’ll do my best.

All right, this here is Kira Rudolph. Oh, that’s no good—‘this here’—you got nothing to work with. No perspective. Why should Kira mean anything to you, right? Okay, I’ll help you out a little more. I’m presently floating above Kira as she’s sitting in her living room. She can’t see me. Now, don’t worry about me, okay, I’m irrelevant. I know the whole invisible-floating thing might peak your curiosity a bit but, really, don’t ask. Kira’s the important one here. I’m just eyes and ears and there’s honestly nothing more to say. Not only am I irrelevant, I am incredibly boring. I have no effect whatsoever on the goings-on here. Cross my heart. Anyway: Kira Rudolph. She’s got a small one-bedroom apartment in the Inner Richmond neighborhood of San Francisco (she’s had it for years—god bless rent-control and a fairly clueless landlord). It’s a bit run down and the building’s kind of terrible but the apartment itself isn’t too bad. Hardwood floors, high ceilings—it was really nice once. Right now it’s 8:30 p.m. (well, 30 and change), daylight saving time. It’s starting to get dark. You know that royal blue you get some nights, for only a few minutes? Well, that’s what we’ve got here. Kira has this huge window—one entire wall of her apartment is pretty much all glass—and she’s up on the fifth floor with no really high buildings around so we’ve got a lot of sky here to look at. Kira hasn’t turned on any lights so it’s just that blue through the window and silhouettes. Nice.

Kira’s twenty-nine years old. She’s, I guess, as they say, ‘of average build’ (maybe a little on the slim side—though that, sadly, isn’t how she sees herself when she looks in the mirror or sits down to eat); her face is basically an inverted triangle, her nose and mouth and eyes all somewhat slight and set close together; she’s got fairly wavy dark hair cut just about mid-back—you know, I don’t think I could ever give a good description to a cop if I were to witness a crime (how do people make those sketches out of words?—it’s a mystery to me). She’s wearing a baggy, dark blue tee shirt, jeans, white socks and no shoes. She’s got sad, sad eyes. She’s an artist and looks it. Enough? Too much, even? No, not too much but maybe focused on all the wrong things. Impersonal. Well, she detests the notion of putting any stock in her looks so I guess you shouldn’t worry about them.

Kira Rudolph’s got her brain out again (now, see, that’s probably how I would have started this thing if I didn’t have a roaring inferiority complex). You can’t see this so you probably think I’m speaking metaphorically (well, writing not speaking but you know what I mean). I’m not, though. Her brain’s on the table and Kira, as she’s often wont to do, is picking at it. Here’s Kira’s problem: she thinks her paintings come from that thing. So she picks at it, looking for the next one. The truth is, too many of her paintings do come from there but none of the good ones. She’ll spend hours picking, untangling, moving bits around searching and the brain will tire of the abuse and come up with something for Kira to do with her paints out of desperation. But it’s just self-defense. That thing doesn’t care what Kira paints. Not when it’s being picked at, anyway. At that point, it just wants to be left alone. So, it’ll come up with something interesting enough to keep Kira’s attention. Something that it can convince her has enough potential to be worth starting. It’s really good at games. It’ll come up with something clever, something ironic and playful and smart. There are usually really good ideas at the edges: something stinging, something that winningly obliterates some pretension some other artist holds dear. Lots of parody. It’s really good at parody.

But, in the end, Kira isn’t satisfied. She’ll laugh along the way, get those lovely little smug-but-not-at-all-mean moments when she’s sure she’s really saying something. Then, inevitably, she gets to that point, far along but not quite finished, where it disappoints her. She’ll step away a little and the painting will feel empty. Its charm will wear off and it will seem, first, not quite so great as it seemed and then it’ll get downright ugly.

So see, not only is this process messy, it’s futile. She slices her scalp, cracks her skull and—jeez—the blood and goo, it gets all over the table. It leaves terrible stains and there’s nothing gets it out. Then the staples and the stitches. All for nothing. Ugh. I float here and watch this gruesome display and I wish I could say something to her.

Her good stuff comes from somewhere else. If it’s clever or otherwise funny or ironic or smart (and often it’s all of those things), that finally isn’t the point. When she’s done, she’ll usually cry. But when there’s nothing to cry about, say she laughs for example, well she laughs; she doesn’t snicker; it’s a hearty, inclusive laughter. When she’s done with a good one, her brain could be on the table or in her head or in the toilet for all she knows because she’s forgotten all about it. Usually, actually, it’s right in her head because she never had to take it out and pick at it. The brain actually gets to enjoy those paintings. The best ones always have plenty of ideas for the brain to play with along with all this other stuff the brain doesn’t understand at all. That’s okay with the brain, by the way; you give it something it can’t figure out, it’ll play with it for days and have a good old time doing it, no matter how futile.

It’s all that other stuff in the good paintings that the brain can’t figure out though that makes them good. It’s stuff that Kira can’t quite put her finger on. I have a hard time with it, myself. There are usually embarrassing things in there: things Kira’s afraid of, in love with, things she does despite her better instincts. There are things Kira knows about herself and the people she loves but her brain doesn’t realize. Her good paintings are filled with things Kira can’t talk about with words but which she must express. She craves those paintings. She needs them.

And she thinks they come from her brain. So she sits there, poor thing, desperately looking for that next brief moment of transcendence. Something tangible and final. There’s a moment, when a good painting is finished, that Kira understands things that are so maddeningly fuzzy the rest of the time. It’s been three months and change since she last had one of those moments. She’s jonzeing something awful.

✦

It is now a quarter to three in the afternoon. Sorry I quit writing. For a while, there was nothing much to write, just poor Kira picking away. When things got interesting, I watched. I thought it best to pay attention and write about it later. Right now, Kira’s finishing up a good painting. It’s lovely to see.

Kira spent a long while messing with her brain. By the time she got to the canvas, it was after midnight and Kira still hadn’t turned any lights on. The only illumination came from the moon and a few streetlights shining through that big window. That was enough, really. She started out doing one of her brain’s pieces. This time it was an angry one. The brain does anger well; it’s an expert. It got Kira thinking about Hetty and that stupid misunderstanding between them. It got her convinced that Hetty no longer cares for her, which is completely untrue and she knows it. Every time she sees her, she knows what Hetty really feels but all it takes is a little bit of distance and her brain gets her scared and, before too long, convinced that any affection she feels from her is imaginary. So, knowing this and desperate to be left alone, her brain got Kira worked up enough to put all that doubt and anger onto the canvas.

Every brush stroke depressed me. You disappoint me sometimes, Kira; you’re so easily manipulated. You’re smarter than that. And you love her. The ugliness on that canvas—the violence—and to know that it was directed at Hetty. In those moments, the canvas was a stand-in for her. Not her body but her psyche, which you wished you could open with your hands—you wanted to leave scars. In moments like that, I wonder why I spend so much time with you. I shout at you, “Get a hold of yourself!” Those are the moments when I most wish that you could hear me. But of course you can’t.

I mean, of course she can’t. I do that sometimes. I find myself inadvertently addressing her in my writing or talking to her out loud. I know it’s pointless. I guess floating up here all the time, above her, watching her and hearing her thoughts makes me want to talk to her. That’s natural. I know her so well, I feel like she should know me. I chatter on and on and then and I realize that I’m thinking of myself as talking to her. But, of course, I’m not talking to her. I’m ‘talking’ to some anonymous soul reading my blog.

So, anyway, she channeled her vitriol onto the canvas for a while. She caught on early this time, though. After a couple of hours, she put down the brush and walked back over to the coffee table. She picked up her brain and brought it over to the canvas. She’s got her canvas set up in front of the big window. Around the canvas are all of her supplies: a little cabinet filled with paint and brushes and scrapers and things like that, lots of little containers for mixing, etc. She plopped the brain down on the top of that cabinet. She got a big, thick brush and covered her brain’s painting with a deep red. The paint from the brain’s work hadn’t totally dried yet so this red got all smeared and mixed up with splotches of browns, blacks, royal blue, yellow and orange. The canvas then looked like a sky during a particularly fantastic sunset.

After that, she dropped her brush into a cup, sat down and waited for the paint to dry. As she waited, she stared at the canvas and everything became clear. She stepped back a few feet and took a good, long look. She smiled. She knew immediately what went where. No picking required. Like with all good paintings, it was a strange kind of knowledge: she couldn’t describe it to you beforehand if you asked and there would be discoveries along the way but there was a shape, an end toward which she would work that was unquestionable. The canvas had an identity. Her hands would know what to do. It wasn’t magic, though, it would take work. The hours of mixing and brushing and re-brushing to follow would have their frustrations and doubts. There would be many moments when Kira would feel like she could never get some bit or another right. The important thing though was that she would know what was right and what wasn’t and that she felt it was the canvas itself that would tell her the difference.

And now she’s done. She’s worked pretty near non-stop all night and through the day (she hasn’t eaten since lunch yesterday—more than twenty-four hours ago) and right now is that strange, difficult, moment when it’s time to put the brush down for the last time. Quite a moment. There’s a long pause before Kira can actually let go of the brush even though she knows it’s done. A thousand mini-questions she knows the answer to but has to ask anyway. It’s thrilling. Lovely. She puts down the brush and steps back.

Oh, she’s crying now. Sobbing. I feel like I should look away and maybe I shouldn’t be writing this as I doubt she’d be terribly comfortable knowing any old person can click a link and vicariously spy in on this very personal moment. I can’t bring myself to look away though and, of course, I can’t control the fact that I hear all the thoughts running through her head right now (it isn’t really sound exactly, at least not that I can cover my ears to—I hear everything; it’s overwhelming sometimes). Her hands are at her sides, useless (dead weight—they, as always, want to be doing something but she has nothing to offer them), her knees are about ready to fall out from under her and in her eyes that sadness she’s been carrying since, oh, since adolescence kicked in at least—it’s gone. I mean, it sounds too simple—pat—but it is; it’s simply gone. You see, she gets it now and it’s completely incredible to her. She’s finally learned that she can pick all she wants and she won’t get anything but jokes and empty thrills. The canvas told her. Or maybe that’s too simple. The wherever-it-is-that-paintings-actually-do-come-from (and, search me, I can’t tell you where that is) told her and she was finally able (open enough, frustrated enough, old enough, experienced enough—who knows?) to understand.

Wow, she really knows. Oh my god, she knows where they do come from. She’s figured out how to find them whenever she needs them. It’s an indescribable sensation: I’m filled with the knowledge of her knowledge but I do not share it. I still don’t know. She can’t send that to me. It’s not comprised of words or of pictures even; it’s knowledge as an entity in and of itself. I know every thought in her head but I can’t know what she now knows. It’s not fair. It’s not fair.

<END>